Key Takeaways

- Space telescope design is governed by aperture size, aberration control, and environmental constraints unique to orbit.

- Refracting systems offer stability but suffer severe aperture limits, while reflecting architectures dominate modern space observatories due to scalability and chromatic aberration elimination.

- Catadioptric designs provide compact, balanced solutions for small to mid-sized missions.

- As space optics evolve, segmented mirrors, active wavefront correction, and hybrid architectures are defining the next generation of high-performance space telescopes.

Introduction: Space Telescopes as Humanity’s Optical Interface to the Universe

Space telescopes represent the pinnacle of modern optical and aerospace engineering. By operating beyond Earth’s atmosphere, they eliminate atmospheric absorption, turbulence, and thermal noise, enabling the detection of extremely faint electromagnetic signals from deep space. In this sense, a space telescope functions as humanity’s interstellar optical eye, extending observational reach toward the origin, structure, and evolution of the universe. From early missions to state-of-the-art observatories such as the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope, space telescopes differ significantly in optical architecture, structural design, and system-level trade-offs. These differences are not arbitrary; they reflect deliberate engineering responses to mission objectives, wavelength bands, and the extreme constraints of the space environment. This article provides a system-level technical overview of space telescopes from three perspectives:- Fundamental optical design principles

- Structural classification of space telescope architectures

- Comparative advantages and limitations of each structural approach

I. Fundamental Optical Design Principles of Space Telescopes

1. Light Collection and Resolution

At its core, a space telescope collects and focuses incoming electromagnetic radiation—primarily in the visible, near-infrared, and ultraviolet bands—onto a detector. Because astronomical sources are distant, incident light can be treated as quasi-parallel, making aperture size the dominant factor governing performance.

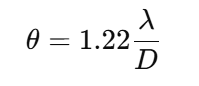

Angular resolution follows the Rayleigh criterion:

where λ is the wavelength and D is the entrance aperture diameter. Consequently, increasing aperture directly improves resolving power and photon collection capability. For example, a 2.4-meter class space telescope operating in visible wavelengths can achieve sub-arcsecond resolution, far exceeding typical ground-based performance without adaptive optics.

2. Aberration Control as a Core Design Challenge

Optical aberrations—spherical aberration, coma, astigmatism, and chromatic aberration—are intrinsic to real optical systems and must be carefully managed. In space telescopes, aberration correction is particularly critical because post-launch optical modification is extremely limited. Key strategies include:- Reflective optics to eliminate chromatic aberration

- Aspheric optical surfaces to suppress spherical aberration and coma

- System-level optimization of field curvature and distortion

3. Environmental Constraints in Space

Beyond pure optical theory, space telescopes must operate under extreme environmental conditions:- Thermal gradients ranging from cryogenic temperatures to near room temperature

- Microgravity, affecting structural preload and alignment stability

- Radiation exposure, influencing material selection and detector longevity

II. Structural Classification of Space Telescope Architectures

From an optical-system perspective, space telescopes can be categorized into three major classes based on the nature of the objective system: refracting, reflecting, and catadioptric architectures.

1. Refracting Space Telescopes

Refracting telescopes form images using lenses and represent the earliest form of astronomical optics. Aberration correction relies on multi-element objective assemblies, such as cemented doublets, air-spaced doublets, and triplet objectives.

While refractors offer high image contrast and stable alignment, their applicability in space is severely constrained by:

- Chromatic aberration inherent to refractive optics

- Manufacturing difficulty of large, defect-free lenses

- Excessive mass and structural length for large apertures

As a result, refracting designs are rarely used in modern space telescopes, with limited exceptions in small-aperture ultraviolet instruments.

2. Reflecting Space Telescopes

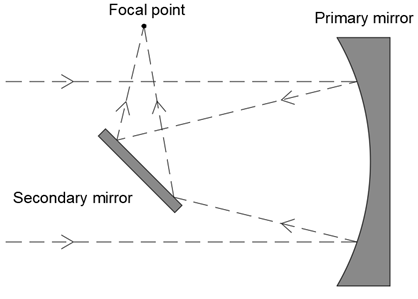

Reflecting telescopes use mirrors as primary optical elements, completely eliminating chromatic aberration and enabling large apertures with manageable mass. This makes them the dominant architecture for professional space observatories.

Common reflecting configurations include:

- Newtonian systems, valued for simplicity but limited by coma and structural length

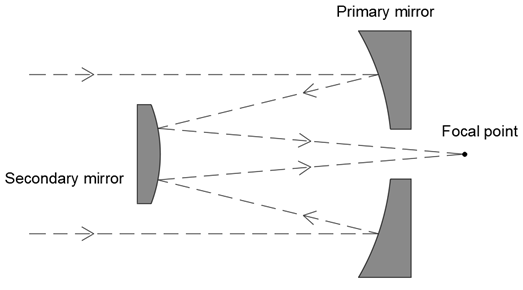

- Classical Cassegrain systems, offering compact form factors and long effective focal lengths

- Advanced aplanatic variants, which significantly improve off-axis performance

Among these, advanced two-mirror systems optimized for aberration suppression have become the standard for research-grade instruments.

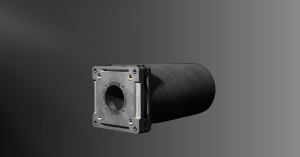

3. Catadioptric Space Telescopes

Catadioptric systems combine reflective primary mirrors with refractive corrector elements. By distributing aberration correction between mirrors and lenses, these designs achieve compact optical paths and high image quality.

Representative configurations include Schmidt-Cassegrain and Maksutov-Cassegrain systems. Their closed-tube architectures provide environmental protection and mechanical stability, making them suitable for small- to medium-aperture space missions and planetary observation platforms.

However, the fabrication complexity of large corrector elements imposes practical limits on achievable aperture size.

III. Comparative Evaluation of Structural Approaches

Architecture | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations |

Refracting | High contrast, stable alignment | Severe aperture and chromatic limits |

Reflecting | Large aperture potential, no chromatic aberration | Alignment sensitivity, thermal distortion |

Catadioptric | Compact, balanced aberration correction | Aperture scaling limitations |

From a system-engineering perspective, reflecting architectures provide the optimal balance between aperture scalability, aberration control, and mass efficiency for deep-space observation missions.

IV. Outlook: Future Directions in Space Telescope Design

The evolution of space telescopes continues to follow three converging trends:

- Larger apertures, enabled by segmented mirrors and deployable structures

- Higher optical precision, supported by active wavefront sensing and correction

- Multi-band integration, allowing simultaneous observation across wide spectral ranges

Future observatories are likely to integrate hybrid design philosophies, combining the strengths of multiple architectural approaches to achieve unprecedented performance within launch and cost constraints.

As these interstellar optical systems continue to evolve, they will remain essential tools for probing cosmic expansion, black hole physics, exoplanet atmospheres, and the fundamental structure of the universe.

Designing a space telescope requires more than optical theory—it demands precision manufacturing, advanced materials, and system-level optimization. If you are developing or evaluating high-performance optical systems for space or aerospace applications, explore our in-depth resources or contact our engineering team to discuss custom optical design, fabrication, and metrology solutions tailored to mission-critical requirements.