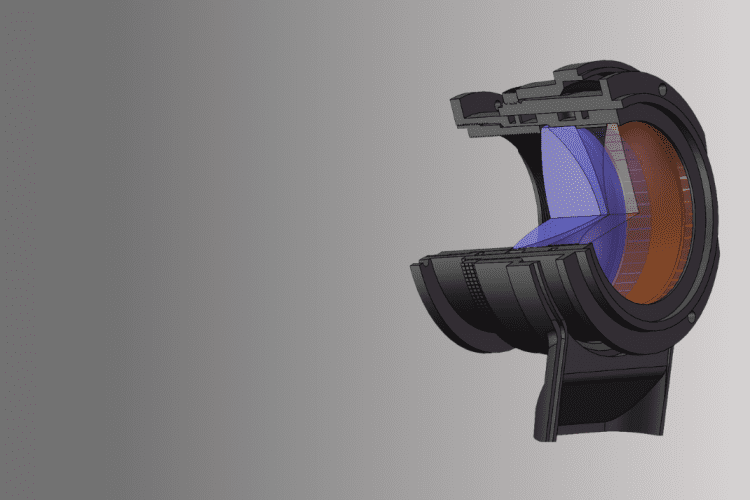

Blurring is a significant source of image degradation in an imperfect imaging system. The optical system’s point spread function (PSF) describes the measure of blur in a given imaging system and is often used in image reconstruction or image recovery algorithms.