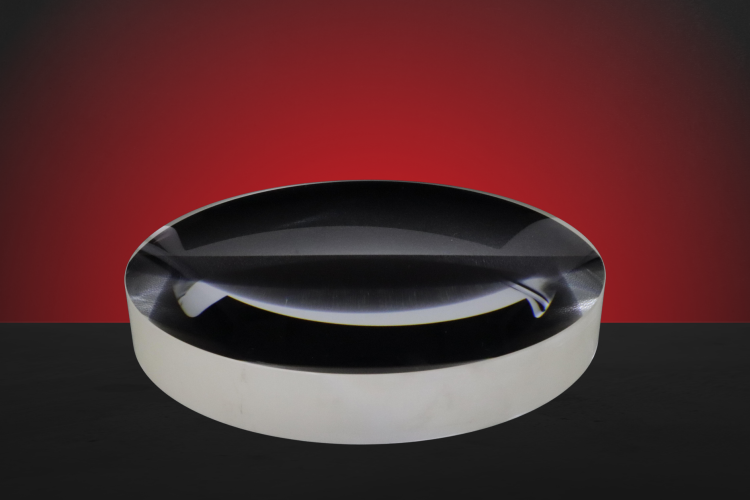

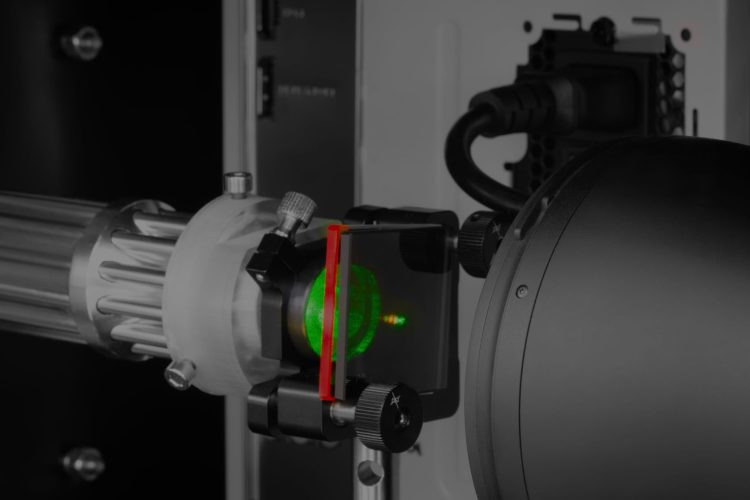

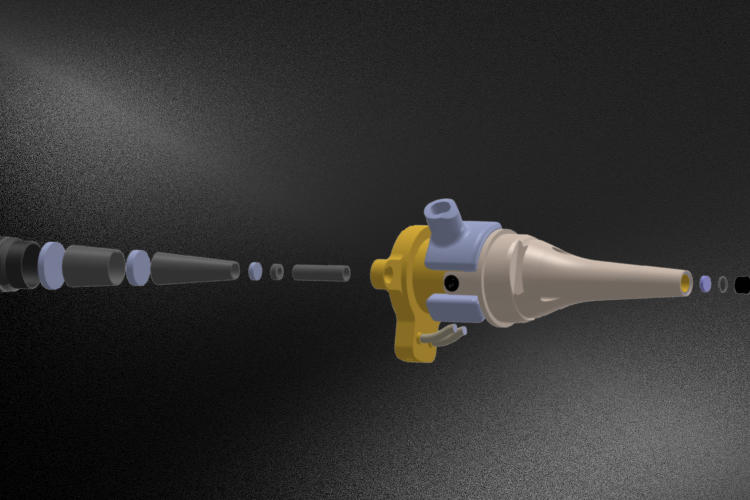

In advanced optical engineering, where precision and performance are pushed to the physical limit, a reliable planar reference defines the success of an entire system. We specialize in manufacturing large-aperture, high-precision flat mirrors that serve as both optical and structural foundations for high-end applications. From astronomical telescopes to high-energy laser systems, our ultra-precision machining and […]