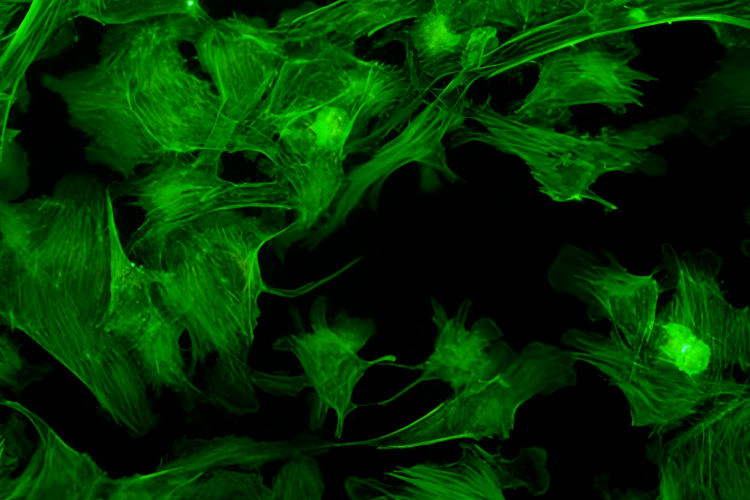

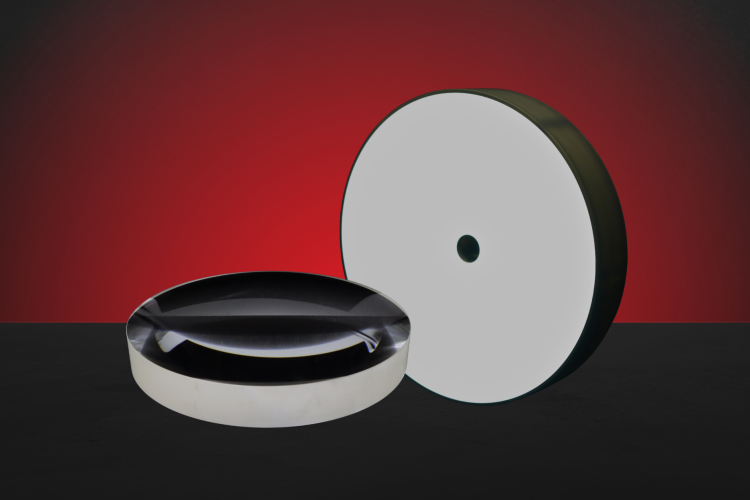

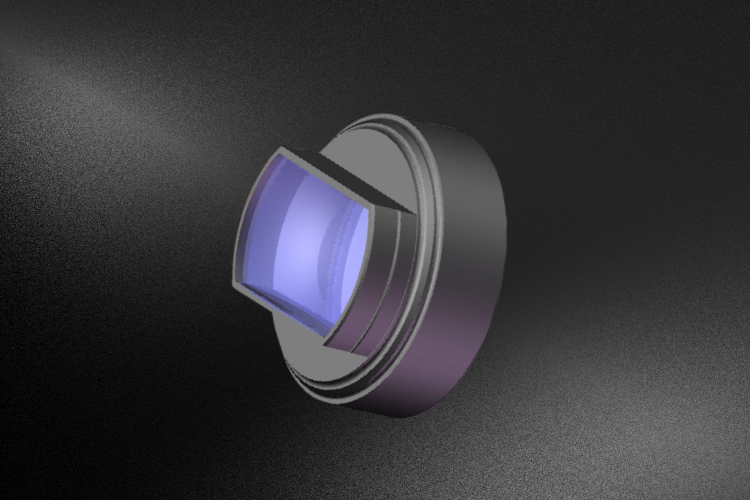

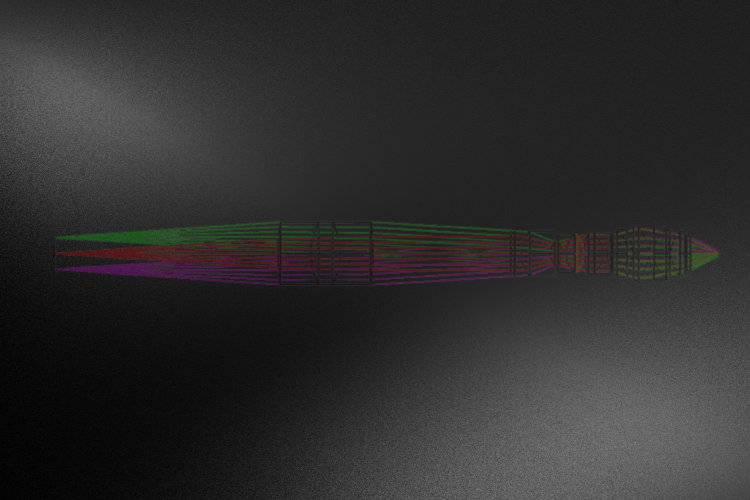

Key Takeaways Fluorescence microscope objectives are specialized optical components designed to maximize light collection and resolution ($0.2mu m$) while minimizing sample damage. Key design factors include high Numerical Aperture (up to 1.49 for oil), multi-band apochromatic correction for labels like DAPI and FITC, and specialized anti-reflective coatings for weak signal detection. In the microscopic realm […]