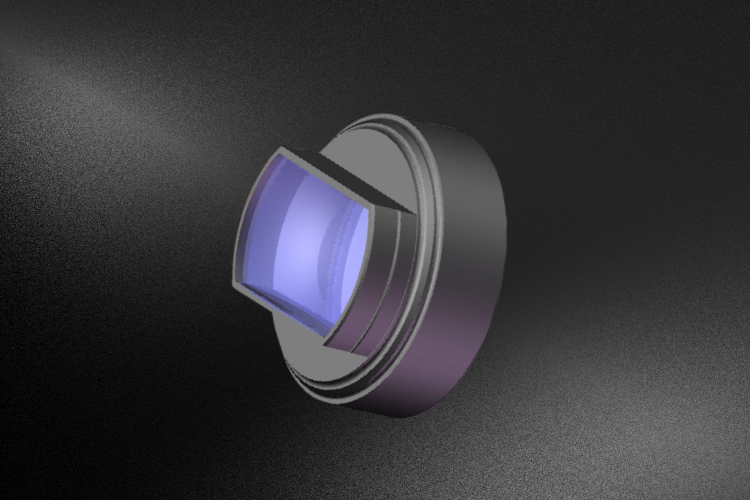

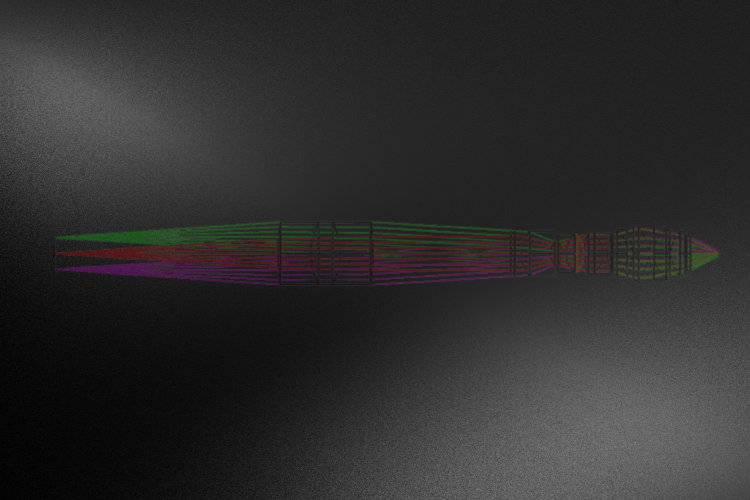

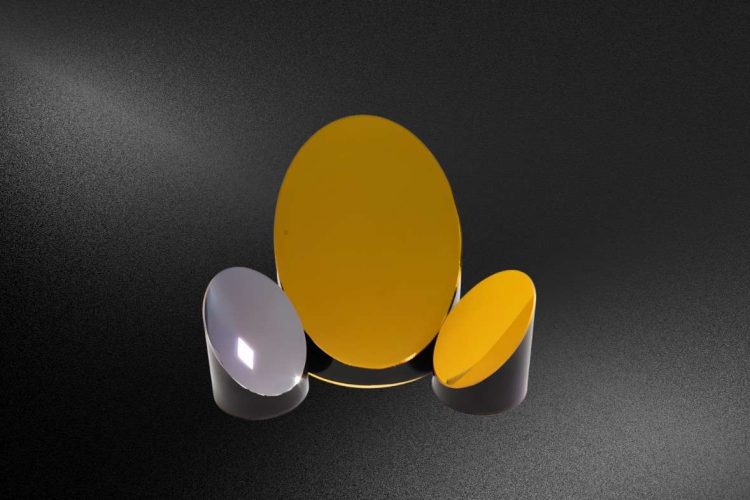

Key Takeaways The Precision Telecompressor optimizes optical systems by intelligently mapping full-frame lens performance onto smaller industrial sensors. By compressing the image field, it restores the native field of view and concentrates luminous flux, providing a one-stop aperture gain and improved Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR). This engineering solution enhances MTF (resolution density) and compensates for sensor-lens […]