Key Takeaways

- Near-infrared (NIR) microscopy objectives (780–2500nm) are essential for “seeing through” opaque barriers.

- By balancing high resolution with superior penetration, they enable deep-tissue biological imaging, subsurface semiconductor defect detection, and non-destructive material analysis.

- Despite design challenges like specialized material selection (ZnS/Germanium) and complex aberration correction, modern NIR optics provide high-transmittance solutions (≥ 85%) that surpass the physical limits of visible light, driving innovation in both high-tech manufacturing and life sciences.

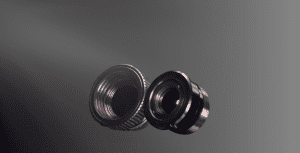

Near-infrared (NIR) microscopy objectives are specialized optical components optimized for the 780 nm to 2500 nm wavelength range. By leveraging the superior penetration of NIR light, minimal phototoxicity to biological tissues, and the ability to capture subsurface material data, these objectives overcome the inherent limitations of visible light. They have become indispensable in fields such as biomedicine, microelectronics manufacturing, and materials science. Their core value lies in the delicate balance of high resolution and wide-spectrum adaptability, providing precise optical solutions for deep-seated imaging requirements.

I. Primary Application Areas

1. Biomedicine and Life Sciences

NIR objectives are the cornerstone of in vivo deep imaging. In the NIR-II window (1000–1700 nm), biological tissues exhibit lower light attenuation and reduced autofluorescence, allowing for significantly deeper penetration.- Deep Tissue Imaging: Multi-photon systems equipped with water-immersion objectives and specialized infrared coatings can penetrate intact murine skulls. Using 1200nm excitation, researchers can achieve 3D reconstructions of cerebral vascular networks at depths of 400 μm, yielding a signal-to-noise ratio far superior to traditional NIR-I imaging.

- Diagnostics: These objectives can distinguish between the morphology of deep-seated healthy vessels and tumorous vasculature, providing critical visual evidence for cancer diagnosis.

- Non-Invasive Analysis: By utilizing the differential absorption rates of NIR light by proteins and lipids, these objectives enable the quantitative analysis of tissue components without the need for destructive physical sectioning.

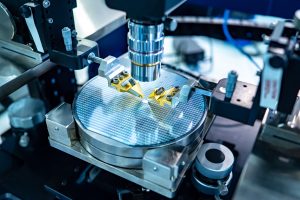

2. Microelectronics and Semiconductor Inspection

In the fabrication of Micro-LED wafers and advanced semiconductor chips, NIR objectives are integrated into Automated Optical Inspection (AOI) systems.- Subsurface Defect Detection: While visible light is limited to surface defects (scratches, photoresist residue), NIR light penetrates the silicon or substrate layers to reveal hidden cracks, bonding voids, and crystal lattice defects.

- Optical Specifications: To achieve high throughput, these objectives often feature an infinite conjugate design, high numerical apertures (NA ≥ 0.3), and wide-spectrum correction (420–1064nm). This allows for an object resolution of approximately 1.5 μm in the NIR band.

3. Materials Science and Cultural Heritage

- Polymer Analysis: NIR microscopy reveals internal stratification, pores, and stress fractures in composite materials, aiding in performance optimization.

- Art Conservation: Conservators use NIR to “see through” pigment and varnish layers, uncovering original charcoal underdrawings or hidden ink traces without damaging the artifact.

II. Engineering Challenges in Design and Production

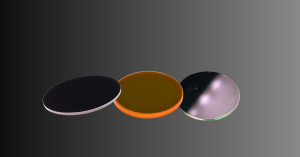

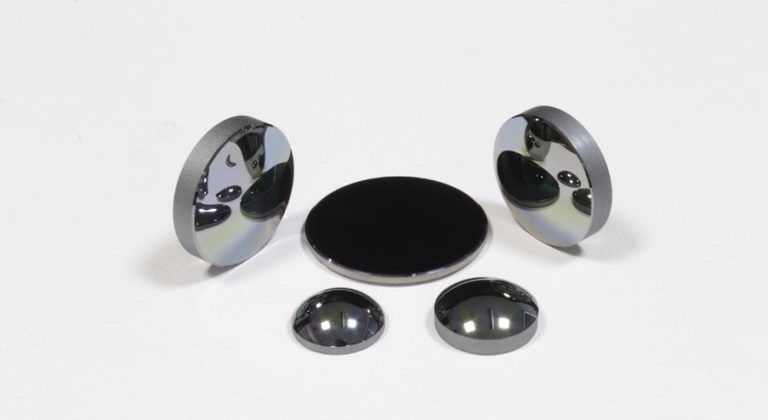

1. Material Selection and Substrate Matching

The NIR region requires materials with high transmittance beyond the range of standard optical glass.- Germanium (Ge): Excellent for mid-NIR, but its brittleness and high thermal expansion coefficient make it prone to stress-induced cracking during precision grinding.

- Zinc Sulfide (ZnS): Often produced via Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD), ZnS offers a highly uniform refractive index (± 0.0002). However, its increased absorption above 10μm and mechanical hardness complicate the polishing process.

2. Aberration Correction and Structural Complexity

Broadband imaging from visible to NIR introduces significant secondary spectrum and spherical aberrations.- Flat-Field Achromatic Design: Achieving a sharp image across the entire field of view (FOV) requires complex lens groupings. For example, Micro-LED inspection often uses a “positive-positive-negative” three-element anti-telephoto structure to correct field curvature and coma while maintaining a working distance of at least 5mm.

- Alignment Precision: Infinite conjugate systems require extreme mechanical tolerances in the lens barrel to ensure the objective and tube lens remain perfectly coaxial.

3. Advanced Coatings and Environmental Durability

Thin-film interference coatings must ensure transmittance of ≥ 85\% across the target bands.- Adhesion Challenges: Multi-layer AR (anti-reflective) coatings often struggle with internal stress and refractive index homogeneity.

- Environmental Sealing: Objectives must be ruggedized for various environments, such as water immersion for biology or extreme temperature fluctuations (-20℃ to +60℃) in industrial cleanrooms.

III. Performance Verification and Metrology

To ensure these objectives meet rigorous industrial and scientific standards, three levels of testing are employed:- Optical Performance: Resolution is verified via the Abbe criterion (target ≤ 1.5μm at 920nm). Wavefront error is monitored using laser interferometry, typically requiring an RMS error < λ/4.

- Geometric Accuracy: High-precision displacement stages verify the working distance within a tolerance of ± 0.1 mm, while resolution plates ensure distortion remains < 0.5%.

- Reliability Testing: This includes thermal cycling, vibration testing to simulate shipping/handling, and immersion seal integrity tests for specialized biological lenses.

IV. Conclusion and Future Outlook

The role of NIR microscopy is expanding as we move toward the NIR-II window and higher numerical aperture designs. Current breakthroughs in material science and multi-layer coating technology are bridging the gap between theoretical optical performance and practical industrial reliability. As these technologies mature, NIR microscopes will continue to provide clearer, deeper, and more precise “insight” into the microscopic world.

Related Content